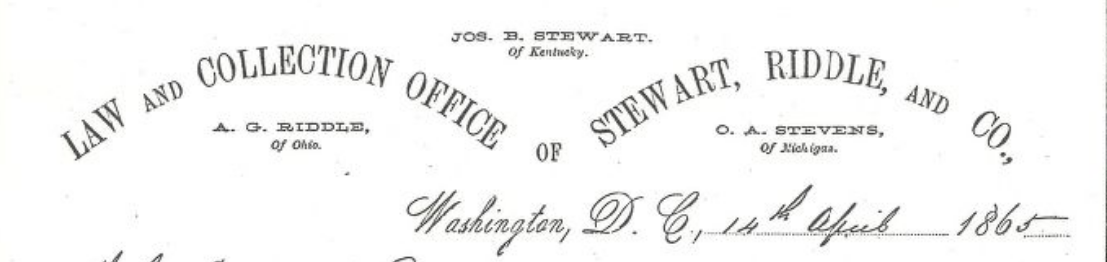

Joseph B. Stewart – of Kentucky

Stewart’s letterhead from letter he sent on the day of Lincoln’s assassination.

As a prominent lawyer from Kentucky, Stewart served as an unofficial liaison in Washington, D.C to his native state in the 1850s – 1860s. He advertised this with his business letterhead listing himself as “Joseph B. Stewart - of Kentucky.” During the Civil War, he created the Kentucky State Agency in the nation’s capital (with himself as chairman) that sought information on captured soldiers behind Confederate lines, and relayed War Department guidance to Kentucky papers. Following are three of his more intriguing encounters in this capacity.

On July 7, 1864 Joseph B. Stewart petitioned President Lincoln on behalf of Patrice de Janon, the professor of Spanish at West Point who was dismissed from his position, sparking a grass roots defense from students, faculty, and notable citizens who believed his removal was unjust. Stewart’s letter to President Lincoln introduced an enclosed communication from George D. Blakey, a pro-emancipation politician from Kentucky who ran for Lieutenant Governor under Cassius Clay’s unsuccessful 1849 bid. Stewart reminded Lincoln that Patrice was married to Blakey’s niece, Mary, and Blakey was “one of the best friends you have in Kentucky.”

President Lincoln had earlier rebuffed Patrice’s attempts to hear his case, and he had responded rudely to Mary when she appealed to him in person. (More on this in a future blog.) Failing to meet Lincoln in-person on this matter, Stewart enclosed his cover letter and Blakey’s letter to Interior Secretary John P. Usher, writing him that Blakey “was a delegate at the Baltimore Convention and will be one of the electors at large at the next presidential election.” With this knowledge, and further impassioned correspondence from Mary de Janon, Lincoln was finally persuaded to reinstate Professor de Janon. This case provides a fascinating lesser- known example of President Lincoln being pulled in opposite directions, and—after not responding initially in the most enlightened way—eventually arriving at the most just conclusion.

Patrice de Janon, West Point professor of Spanish

A few days after President Lincoln’s assassination, there were obscure newspaper references to a “Meeting of Kentuckians” in the capital to form a committee for Lincoln’s funeral, noting “J.B. Stewart and Colonels [Taliaferro P.] Shaffner and Duncan were appointed a committee to carry the arrangements into effect.” Colonel Shaffner had worked with Samuel B. Morse on telegraph projects in the Atlantic and in Russia, and had also worked with Stewart in a business venture involving Alfred Nobel—the inventor of dynamite. Two days later, Stewart—as Chairman of the Kentucky State Agency—posted a notice in the National Republican calling for Kentucky citizens to gather the following morning at his office building to attend President Lincoln’s funeral.

In Stewart’s testimony for the Lincoln assassination, one portion remained secret from the public until the 1930s concerning a couple of Kentuckians named Payne who visited his law office in November 1864 and who divulged various anti-Union plots. At the time of his statement, Lewis Powell, operating on the alias of Paine (but transcribed as Payne) was the mystery conspirator—leading to much speculation about possibly related Paynes operating in the United States and Canada. Stewart recollected discussing the matter with Garrett Davis, the U.S. Senator from Kentucky, at the time, and also attempting to warn the Treasury and War Secretaries. Why was this evidence classified, and what came of it?

Learn more about this mysterious group of Kentuckians, and Stewart’s appeal to Abraham Lincoln on behalf of Professor Patrice de Janon, in the upcoming book Almost in Reach of Fame: Joseph B. Stewart, the Bourbon Giant who Chased Lincoln’s Assassin and Caught Scandal.

Sources:

Letter from Mary de Janon to Abraham Lincoln, Feb. 10, 1864, Abraham Lincoln papers: Series 1. General Correspondence. 1833 to 1916, Library of Congress

Joseph B. Stewart to Abraham Lincoln, July 7, 1864, Abraham Lincoln Papers: Series 1. General Correspondence. 1833 to 1916, Library of Congress.

Joseph B. Stewart to John P. Usher, July 7, 1864, Abraham Lincoln Papers: Series 1. General Correspondence. 1833 to 1916, Library of Congress.

Mary de Janon to Abraham Lincoln, Aug. 15, 1864, Abraham Lincoln papers: Series 1. General Correspondence. 1833 to 1916. Library of Congress.

“Telegraphic News,” Courier Journal (Louisville, Kentucky), April 18, 1865, p. 3.

National Republican, April 18, 1865, p. 2.

William C. Edwards and Edward Steers, eds., The Lincoln Assassination: The Evidence, (Champaign, Illinois, 2009).