Lincoln in Harrisburg: A Tale of Two Trains

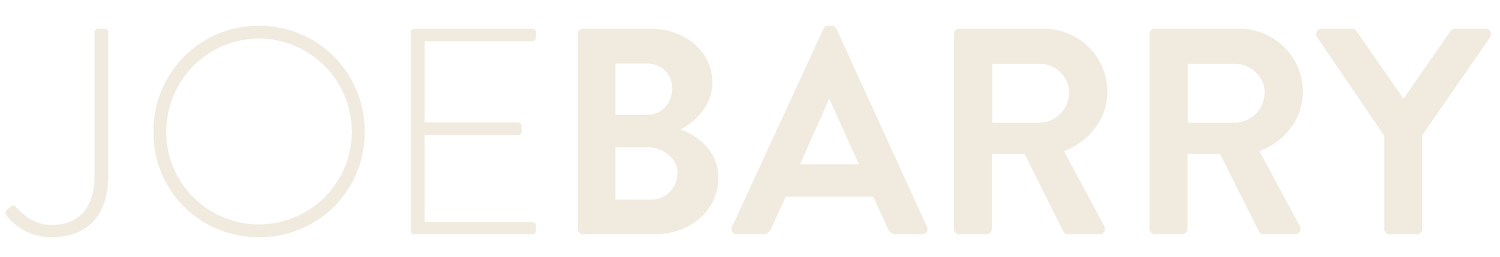

Lincoln’s Train in Harrisburg, April 21, 1865

A recent meeting with my company in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania inspired me to conduct historical research on President Abraham Lincoln’s two unique visits to this city. Knowing only the basic outlines, I dug deeper, and what I found reminded me that history is everywhere—and often closer than you realize.

* * *

Three weeks prior to his inauguration on March 4, 1861, President Lincoln embarked on a 1,900-mile railroad journey from his home town of Springfield, Illinois to the nation’s capital. Newspapers published the route involving sixteen cities, and the president-elect found an audience at each stop expecting him to deliver comments. He obliged with small speeches, amusing anecdotes, and jokes—delivering them from the edge of the train, at train stations, from hotels, and at capitol buildings. In the middle of one of Lincoln’s jokes at Thorntown, Indiana, his train pulled away before he could deliver the punchline, causing an uproar of laughter.

Events took a more serious turn, however, when the detective Allan Pinkerton discovered a plot against Lincoln’s life in Baltimore. Captain Cypriano Ferrandini, a revolutionary from Corsica who worked at Barnum’s Hotel in Baltimore (a hotspot for successionists), reportedly declared in a crowded room of similar-minded conspirators that Lincoln would never get to Washington, D.C. alive. Far from hiding these views, two weeks earlier Ferrandini had testified before a congressional select committee investigating threats to the inauguration—avowing he would prevent Lincoln from passing through Maryland. Pinkerton and his agents gained Ferrandini’s confidence and learned the inner workings of the plot.

The would-be assassin Cypriano Ferrandini

In Pinkerton’s estimation, he had to act fast. He raced to Philadelphia and on February 21st he met with Lincoln to persuade him to skip his Harrisburg stop and pass through Baltimore a day earlier than scheduled. Lincoln disapproved, as he had promised to raise the flag at Independence Hall the following morning and address the legislature at Harrisburg in the afternoon. Lincoln was somewhat skeptical of the threat—until that evening when Frederick Seward brought a letter from his father and future Secretary of State, William H. Seward, warning of the same plot.

Pinkerton revised the security plan, calling for Lincoln to depart Harrisburg on a separate train and arrive in Baltimore earlier and on a different track and station. In agreeing to this change, Lincoln mused, “I suppose they will laugh at us.” This would be a huge understatement.

At 1:30 p.m. on February 22, 1861, Lincoln arrived at Harrisburg. The Harrisburg Telegraph reported “a dense mass of humanity” waiting to greet the president-elect, including “the music from twenty bands, the loud roar of cannon, and the wild huzzas from twenty thousand throats.” Lincoln and his entourage took a short carriage ride pulled by six gray horses to the Jones Hotel on Market and Second Street, where he addressed the crowd from the portico. Noticing a large contingent of military men, Lincoln noted:

Allow me to say in regard to those men that they give hope of what may be done when war is inevitable. But, at the same time, allow me to express the hope that in the shedding of blood their services may never be needed, especially in the shedding of fraternal blood.

Ironically, on the very grounds where Lincoln stood, President George Washington had stayed at a house in October of 1794 on his way to put down the Whiskey Insurrection.

Jones House in Harrisburg, PA

One hour after his arrival in Harrisburg, Lincoln visited the Capitol Building. In front of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives he repeated his desire to avoid shedding fraternal blood, adding: “I promise that, in so far that I may have wisdom to direct, if so painful a result shall in any wise be brought about, it shall be through no fault of mine.”

After his speech, Lincoln returned to the Jones House where Pennsylvania governor Andrew Curtin accompanied him for dinner. Curtin was privy to the secret plan to send Lincoln off early. After dinner ended at 5:45 p.m., he called for a carriage to take him and Lincoln to his executive mansion—but this was a ruse. In reality, the governor took Lincoln out a side door where the actual carriage was waiting. Lincoln’s self-appointed bodyguard, Ward Lamon, ensured the party entered without incident. To conceal himself, Lincoln donned a beaver hat one of his friends from New York had gifted him, as well as an overcoat and a shawl. It was a short carriage ride to his rendezvous location for the special train that would whisk him away to Washington.

The carriage driver for this secret mission was Jacob T. Compton, the personal coachmen to U.S. Senator and future Secretary of War Simon Cameron. During the Civil War, Compton served in the 100th Pennsylvania U.S. Colored Troops and the 24th U.S. Colored Infantry Regiment that guarded the nation’s capital.*

Accounts differ as to where Lincoln boarded the special train. One version has him boarding at the station on the corner of Second and Vine (the same location he arrived earlier in the day). Other accounts have the train on the intersection of Front Street where the train tracks intersect at present-day Mulberry Street.

Approximate area where Lincoln’s secret train departed

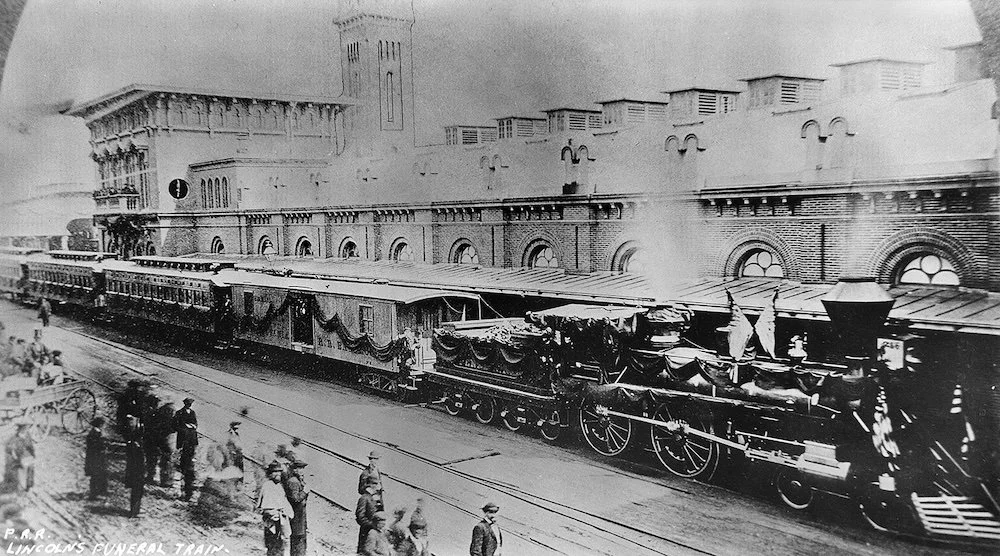

After Lincoln’s special train departed, his team left nothing to chance. Pinkerton ordered the telegraph lines cut between Harrisburg and Baltimore. Governor Curtin refused any visitors that evening to create the impression Lincoln was resting inside the executive mansion. The special train arrived in Philadelphia at 10:00 p.m., an hour earlier than planned. Lincoln de-trained with Pinkerton and Lamon—stooping down as he walked to mask his tall frame. They travelled via carriage to the Baltimore-bound train station three miles away.

At 3:30 a.m., Lincoln’s train arrived in Baltimore without incident. But the most dangerous portion of the trip remained with a one-mile ride to the Camden Street Station connecting with the final train into Washington. Even worse, this connecting train was delayed—forcing an agonizing wait. Ultimately the Baltimore & Ohio train arrived with Lincoln and his team pulling into Washington, D.C. at 6:00 a.m. on February 23, 1861.

Frank Leslie’s Weekly sketch on Lincoln passing through Baltimore

Before the diversion was made public, Lincoln’s regularly scheduled train stopped through Baltimore later that morning—also without incident. Were the conspirators tipped off, or did they get cold feet? Was Pinkerton’s intelligence self-serving, or an overreaction to the bluster of a big talker? Historians remain of mixed opinion. There was, to be sure, a heavy police presence that may have deterred any would-be conspirator.

The tactical success of this mission came at a steep political cost. The Baltimore mayor and a respectable crowd waited to greet Lincoln in vain, and they were incensed at the snub. Reporters had a field day with this news. What did it say for the state of the Union that the incoming president had to sneak into his own capital? Lincoln’s detractors across the nation ridiculed him—with some going so far as to claim he wore a woman’s dress on the train. Remembering the ridicule, Lincoln lowered his guard throughout his presidency, and Lamon often struggled to protect him during his frequent public appearances.

Lincoln’s detractors letting their imaginations run wild

President Lincoln would make a second trip by train to Harrisburg four years later under tragic circumstances. After his assassination on April 14, 1865, a funeral train bearing his coffin travelled from Washington, D.C. to Springfield in reverse order of his inaugural trip. At 8:30 a.m. on April 21, 1865, his funeral train stopped at Harrisburg amid heavy rain, thunder, and lightning. Four white horses pulled the hearse with his coffin to the capitol building. Governor Curtin was again part of the ceremony, joined by 30,000 mourners throughout the city.

The worst fears of 1861 had dreadfully materialized. Unsurprisingly, John Wilkes Booth and a number of his fellow conspirators originated from or operated in Baltimore and southern Maryland. Ward Lamon, who was in Richmond the day of the assassination, could only lament: “As God is my judge, I believe if I had been in the city, it would not have happened and had it, I know that the assassin would not have escaped the town.”

If only.

April 21, 1865: A wet, somber day in Harrisburg

* * *

Before conducting this research, I was interested to know exactly where in Harrisburg these events took place. Lo and behold, the Jones House stood on the very grounds of the Penn National Insurance Building where my company is located. I had actually walked past the historical sign for the Jones House several times without bothering to read it.

As much as life demands us to occasionally stop and smell the roses, it also demands we slow down and explore the history on the very ground we walk upon.

Learn more about the Lincoln assassination in my upcoming book, Almost in Reach of Fame: Joseph B. Stewart, the Bourbon Giant who Chased Lincoln’s Assassin and Caught Scandal. Stewart was the “Forrest Gump” of the nineteenth century who gave chase to John Wilkes Booth at Ford’s Theatre.

Sources:

* This account is based on Compton’s obituary in 1905. Another account has George C. Franciscus, a superintendent of the Pennsylvania Railroad, driving the carriage.

Daniel Stashower, “The Unsuccessful Plot to Kill Abraham Lincoln,” Smithsonian Magazine, Feb. 2013, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-unsuccessful-plot-to-kill-abraham-lincoln-2013956/, accessed July 22, 2025.

“The Baltimore Plot,” Ford’s Theatre, National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/foth/baltimore-plot.htm, accessed July 25, 2025.

Erik Larson, The Demon of Unrest: A Saga of Hubris, Heartbreak, and Heroism at the Dawn of the Civil War (New York, 2024), 234.

Harrisburg Telegraph, Feb. 22, 1861, p. 4.

Patriot-News (Harrisburg, PA), Feb. 23, 1861, p. 2.

Harrisburg Telegraph, April 24, 1865, p. 1.

Kylie Smith, “Jacob T. Compton: The Musician, Sergeant, and President’s Coachman,” Harrisburg Historical, https://harrisburghistorical.org/items/show/13, accessed July 22, 2025.

“Noted Coachman Dies,” Harrisburg Telegraph, Sep. 7, 1905, p. 6.

“The Jones House,” Historical Marker Database, https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=6550, accessed July 30, 2025.