Will research for peanuts!

Who Really Held John Wilkes Booth’s Horse?

I am excited Dave Taylor, creator of LincolnConspirators.com, is featuring my article on his site. If you are fascinated with the Lincoln assassination, his site is worth frequently visiting. I am also a Patreon supporter of Dave—trust me, he produces awesome content.

ONE OF THE MORE ENIGMATIC FIGURES of the Lincoln assassination is Joseph “John Peanuts” Burroughs, the young errand boy at Ford’s Theatre who held John Wilkes Booth’s horse prior to the assassin’s escape. Burroughs’s age is unknown, although estimates vary between fourteen to seventeen years old. In his statement to Justice Abram Olin on April 15, 1865, his name was dictated as Joseph Burrough. However, the conspiracy trial records also list Borroughs, Burrow, and John C. Bohraw—which are likely phonetic transcription errors. At the theater, he soon earned the nickname “John Peanuts” because he peddled peanuts in between acts. Some newspapers after the assassination even misreported “John Peanuts” as “Japanese.”[1]

Burroughs’s experience in the assassination was brief and traumatic. After Booth asked for the stagehand Edman “Ned” Spangler to hold his horse, Spangler begged off owing to his scene shifting duties, and the task fell to Burroughs. After approximately fifteen minutes, Booth burst through the back door into Baptist Alley and rewarded Burroughs’s loyalty by hitting him on the head with the butt of his knife and kicking him away from his horse. Across Peanut’s multiple pieces of testimony, he described handling horse-related duties for Booth over the previous few months, of working with Spangler in fixing the president’s box at Ford’s Theatre, and of Spangler cursing the president over the war.[2]

Throughout the years, a consensus emerged Burroughs was Black and dull-witted. The best evidence indicates he was neither. Burroughs signed his second statement on April 24th with an “X”, which could suggest he was illiterate, but his testimony reveals he was intelligent, articulate, and well-versed with horses. The orchestra director, William Withers, and former police superintendent, Almarin C. Richards, both described him as Black, but these accounts were decades old. More conclusively, the trial transcripts for Burroughs lack the “(Colored)” description preceding his name in keeping with the discriminatory practice of the period. John F. Sleichmann, the assistant property manager at Ford’s Theatre, testified that Booth, Burroughs, and a few others shared drinks at the nearby saloon on the day of the assassination. Yet, Blacks were not allowed to sit down in such restaurants at this time, and an inveterate racist like Booth would not associate with a Black person. Nevertheless, contemporary newspaper illustrations depicted Burroughs as Black.[3]

Joseph Burroughs watching Joseph B. Stewart chase Booth out Ford’s Theatre

In American Brutus, Michael Kauffman theorizes Burroughs was the son of Doctor Joseph Borrows, III, a prominent physician in Washington, D.C. In his April 24th statement, Burroughs stated he was living with his father at 511 Tenth Street. Although this corresponds to the Ford’s Theatre address since at least 1948, prior to 1869 this address was south of Pennsylvania Avenue near the present-day block of 317-337 Tenth Street NW. The address for the Army Medical Museum in 1868 (housed within the theater building) was 454 Tenth Street. Notably, the city directory listed Dr. Borrows’s address as 396 E Street north, which abutted Baptist Alley behind Ford’s Theatre. The Borrows name and his close proximity to the theater make for a compelling connection—even if it does not illuminate Burroughs’s subsequent actions and movements.[4]

However, the Dr. Borrows theory has shortcomings. The reference to Peanuts living with his father implies the mother was absent. Yet, Dr. Borrows had a wife, Catherine, who outlived him. Further, the 1860 census for the Borrows household includes four females, but no son. Tragically, Catherine delivered a stillborn boy, Joseph, in 1850—a year after their five year-old daughter died. As author Susan Higginbotham has noted, a doctor’s son would be in school and not selling peanuts and running errands at a theater.[5]

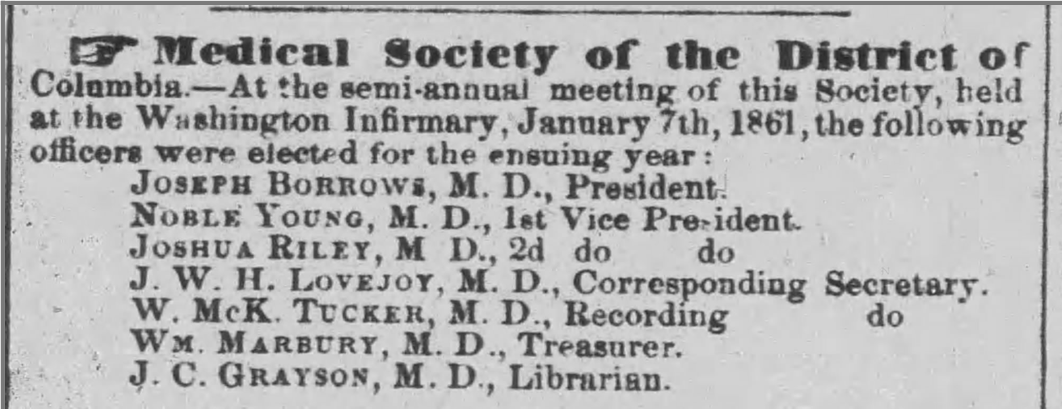

Even still, Dr. Borrows’s obituary in 1889 provides a clue that may explain a potential connection with Peanuts. The doctor was an eminent physician who served for several years as president of the Medical Society of the District of Columbia. His obituary in the Evening Star notes: “There was probably no more popular physician or man in the District than Dr. Borrows, and hundreds of children were named for him in families he attended through, in some instances, four generations.” It is possible Burroughs received assistance from Dr. Borrows and perhaps even stayed at his residence in the same itinerant manner as at Ford’s Theatre. Similarly, Ned Spangler kept a boarding house for supper but mostly slept inside Ford’s Theatre.[6]

Dr. Joseph Borrows was a leading Washington, D.C physician, Daily National Intelligencer, January 9, 1861

To read the remainder of the article, visit LincolnConspirators.com

Learn more about Joseph B. Stewart, his chase of John Wilkes Booth, and his interaction with Peanuts in my upcoming book Almost in Reach of Fame: Joseph B. Stewart, the Bourbon Giant who Chased Lincoln’s Assassin and Caught Scandal.

NOTES

[1] The official record of the commission compiled by Benn Pitman lists the name as Joseph Burroughs. The conspiracy trial transcripts show multiple references to Peanut(s), John Peanut(s), and Peanut(s) John. Michael Kauffman also cites Bohrar and Burrus in American Brutus. “The Assassination,” Daily Illinois State Journal, April 22, 1865, p. 1.

[2] Peanuts stated he held the horse for fifteen minutes at the conspiracy trial, although this is different from his provided statements. Burroughs’s testimony at the conspiracy trial is found at Edward Steers, Jr., ed., The Trial: The Assassination of President Lincoln and the Trial of the Conspirators (Lexington, Kentucky, 2003), 187-95, 465-66; William C. Edwards and Edward Steers, eds., The Lincoln Assassination: The Evidence, (Champaign, Illinois, 2009), 238;

[3] William J. Ferguson’s 1930 memoir I Saw Booth Shoot Lincoln refers to Peanuts as “dull-witted.” Joan L. Chaconas, “Will the Real ‘Peanuts’ Burroughs Please Rise?!” Surratt Courier (June, 1989), 1, 3-7; “Wilkes Booth Again,” Critic (Washington, D.C.), April 17, 1885, p. 1.

[4] Washington, D.C. addresses changed to a new format in 1869. William H. Boyd, Boyd’s Washington and Georgetown Directory, 1868(Washington, D.C., 1868), 40; Edwards, Steers, The Lincoln Assassination, 463; Andrew Boyd, Boyd’s Washington and Georgetown Directory, 1865 (Washington, D.C., 1865), 142.

[5] “More on the Elusive Peanuts,” Surratt Courier (September, 2014), 11; 1870 US Census, Washington, D.C., Ward 3, family 220; “Dr. Joseph Borrows,” Find A Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/140486080/joseph-borrows.

[6] Emphasis added. The Ned Spangler information is from Jacob Ritterspaugh’s testimony. “Dr. Joseph Borrows Dead,” Evening Star, May 31, 1889, p. 3; Steers, The Trial, 394.